Black Woman, Unwritten: On the Necessity of Writing

An essay and a poem on writing and unwriting and rewriting

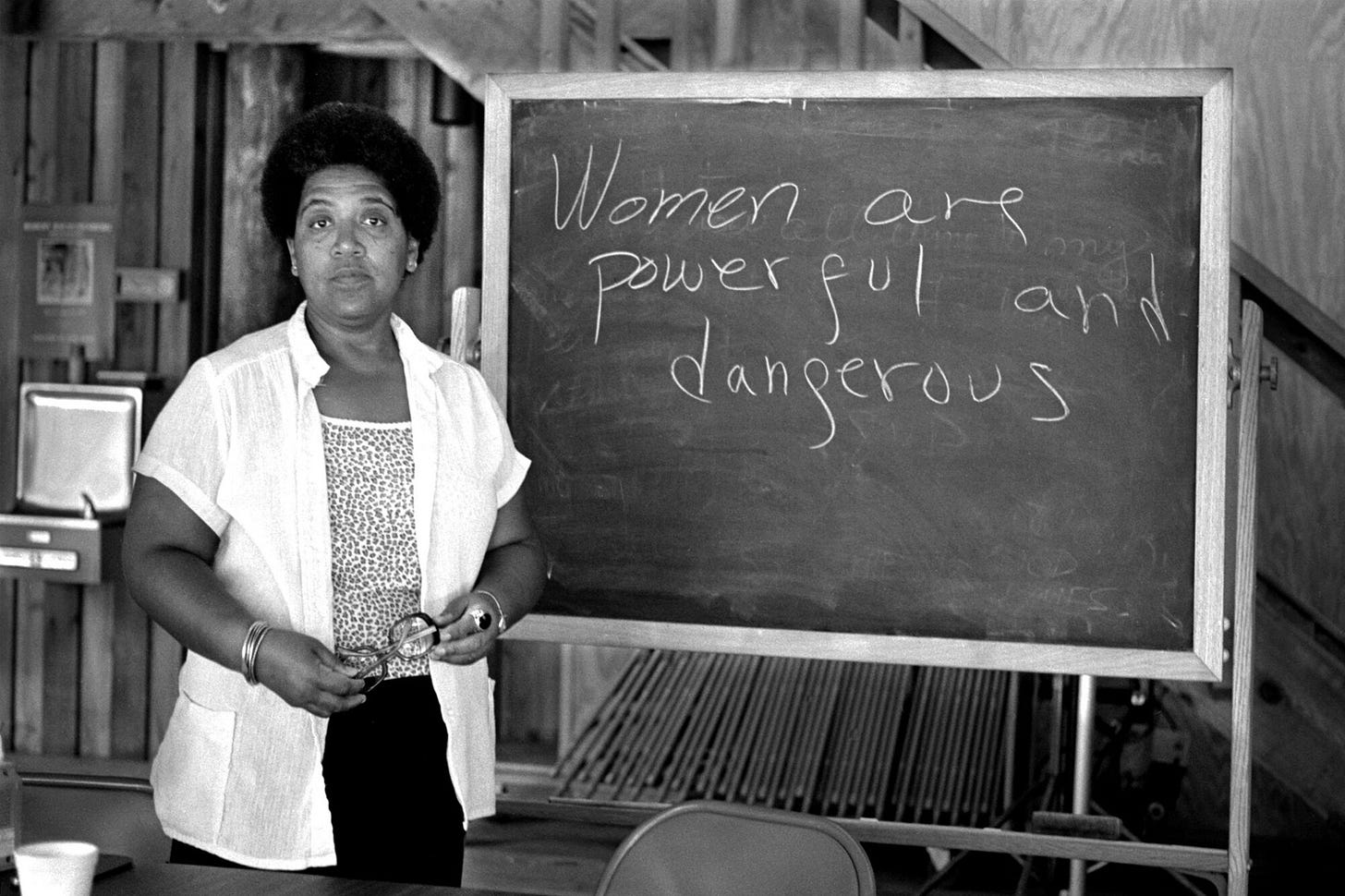

The introduction to Toni Morrison’s The Source of Self-Regard ends with the following line: “A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity.”1 Like a wave, my mind crashed back against a quote from Audre Lorde: “For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence.”2 The recurrence of the idea of writing as necessity from two prolific Black women writers is no small matter; it is a truth whose weight is not quite considered, is not quite understood.

For women, for Black women, for marginalized people everywhere, writing cannot afford to be a pastime or a passing interest or a luxury as Lorde rejects. For people whose voices have historically been undervalued, forgotten, erased, or unheard, writing is as liberating as the breaking of a chain or unclasping one’s bra at the end of the day or waking up on a weekend with nowhere at all to be and nothing to do. For Black women especially, I believe writing is primarily an act of reclaiming and recontextualization of our history in America.

For Black women, much of our writing is, in fact, unwriting. Before brown fingers can begin with the great and terrible I, she must first unwrite over four hundred years of sexist-racist3 mythology. She must unwrite the Jezebel, the Mammy, and the Sapphire. She must rip off Aunt Jemima’s apron and close Jezebel’s legs (or keep them wide open) and bury the Sapphire under the earth of her need.

But what does the Black woman need? What does the Black woman writer need? I can only speak for myself as person, as woman, as girl: I need someone to hear me. Whether I am screaming or singing, I need someone to hear me. Being seen feels too intimate, almost disturbing in a way—like a dead deer on the side of the road, its insides exposed to an unwilling audience. For so long I have felt much like a carcass with the world as a wake of vultures feeding on my hurt. The biggest vultures, of course, being the people most close to me.

Unfortunately, I have grown accustomed to the picking, to the sharp beak of judgment, to the messiness of the eating. I hate being seen because the human eye eats everything—swallows what it wants and spits out the rest. What the eyes spit out is often the self I admire; what the eyes digest is often the self I despise. At worst, what the eyes digest is exactly what anti-Black racism has fed them from birth. It is a privilege to be able to write without having to unwrite anything because no one else had thought they could tell your story for you; this is not a privilege Black women have.

The little we have and know of our history as Black women has been largely reported by white people—particularly white men. After white people, Black men have mainly been the ones to speak on the Black experience and, therefore, what society largely considers to be the Black experience is, in fact, the Black male experience. As such, we are often relegated to supporting positions such as mother, aunt, grandmother, sister, daughter, love interest or—at worst—enemy. Because white people and Black men have never experienced the dual oppression of being both non-white and female, none of these groups of people have any real authority to document or speak on the lived experiences or histories of Black women—or to speak over Black women.

These are only a few reasons why writing is a “vital necessity” as Lorde claimed. It is vital for Black women to unwrite the cruel mythology of America and it is a necessity for us to rewrite the truth. I define “the truth” in this context not as something concrete, but as something volatile. What was or is true for me is not or was not true for every Black woman—but it is certainly a truth.

At first, I wrote as a form of escapism. I wrote because I wanted to have something I could control. I resisted poetry. I resisted nonfiction. I associated essays with schoolwork—with historical and literary analyses about subjects I didn’t truly care about or find interesting. Discovering Black women writers like bell hooks, June Jordan, Lucille Clifton, and, of course, Audre Lorde—and their multifarious truths—has allowed me to recognize how writing can be a weapon against empire as well as a tool for self-realization. Reading their work allowed me to understand the “vital necessity” of poetry, the essay, and the inherent power of the lyric I. When I was younger, I resisted my I because I didn’t know it could be a tool of defiance, of affirmation, of liberation. I didn’t believe I mattered—but the I must matter if we want to become a future we.

Morrison, Toni. “Peril.” The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations. New York, Vintage Books, 2019.

This quote is from the essay “Poetry is not a luxury” by Audre Lorde.

The term “sexist-racist” is borrowed from bell hooks.

This whole piece was healing. Thank you Zi, for the poem which is such small words speaks volumes and the essay, which encourages me and reminds me of our duty, to survive. To write is to continue surviving. You’re very talented

This was incredibly beautiful and reassuring.

Hanif Abdurraqib wrote, "If we don't write our own stories, there is someone else waiting to do it for us." And that is incredibly true for us as black women. For many, many years, we had to fight to even be seen as women. I am grateful to live in this time period where I can read so many wonderful Black women writers and see myself on the page. This piece also encouraged me to get back into writing! Writing has always been the medium I felt the most intimate with because I never felt that I could express myself in any other way that mattered.

Tressie McMillan Cottom mentioned in her book Thick that the personal essay is the domain that Black women should claim because of our voices and experiences have so often been undermined and silenced.

Thank you so much for this. I'm going to get back into writing and having confidence in my own experiences and stories!